Private data

What is private data?

In cases where a group of organizations on a channel need to keep data private from

other organizations on that channel, they have the option to create a new channel

comprising just the organizations who need access to the data. However, creating

separate channels in each of these cases creates additional administrative overhead

(maintaining chaincode versions, policies, MSPs, etc), and doesn’t allow for use

cases in which you want all channel participants to see a transaction while keeping

a portion of the data private.

That’s why Fabric offers the ability to create

private data collections, which allow a defined subset of organizations on a

channel the ability to endorse, commit, or query private data without having to

create a separate channel.

Private data collections can be defined explicitly within a chaincode definition.

Additionally, every chaincode has an implicit private data namespace reserved for organization-specific

private data. These implicit organization-specific private data collections can

be used to store an individual organization’s private data, which is useful

if you would like to store private data related to a single organization,

such as details about an asset owned by an organization or an organization’s

approval for a step in a multi-party business process implemented in chaincode.

What is a private data collection?

A collection is the combination of two elements:

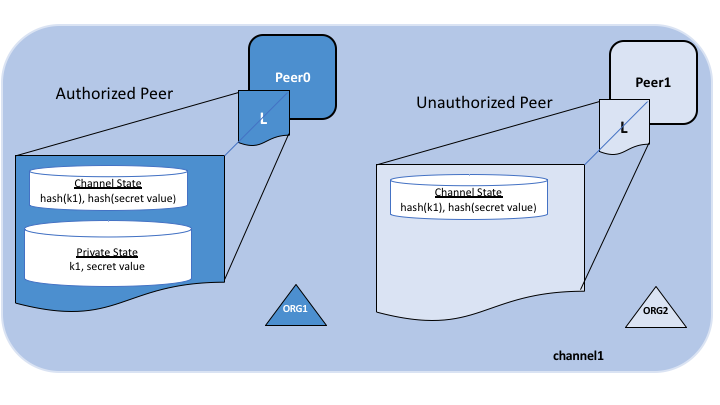

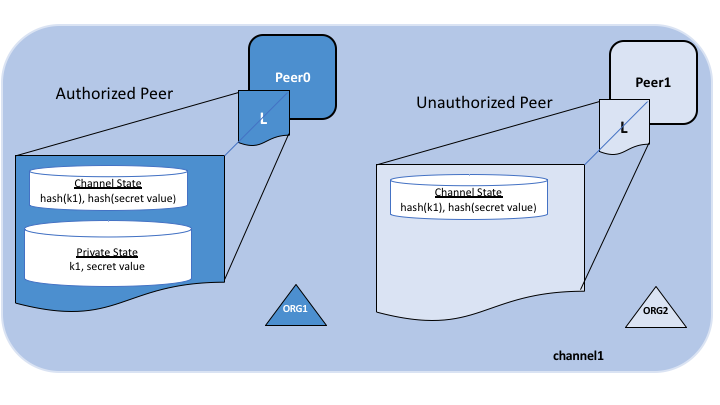

The actual private data, sent peer-to-peer via gossip protocol

to only the organization(s) authorized to see it. This data is stored in a

private state database on the peers of authorized organizations,

which can be accessed from chaincode on these authorized peers.

The ordering service is not involved here and does not see the

private data. Note that because gossip distributes the private data peer-to-peer

across authorized organizations, it is required to set up anchor peers on the channel,

and configure CORE_PEER_GOSSIP_EXTERNALENDPOINT on each peer,

in order to bootstrap cross-organization communication.

A hash of that data, which is endorsed, ordered, and written to the ledgers

of every peer on the channel. The hash serves as evidence of the transaction and

is used for state validation and can be used for audit purposes.

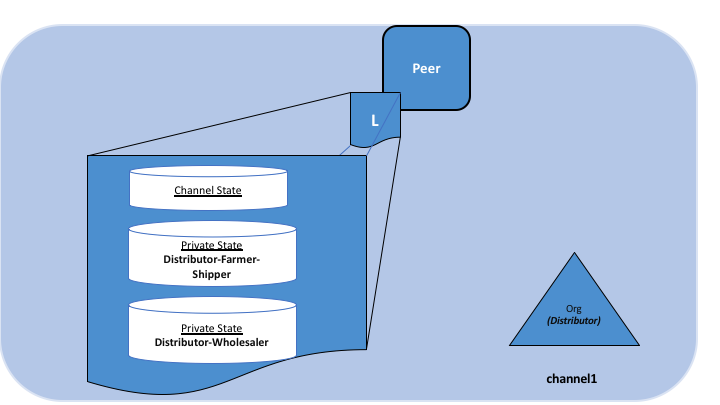

The following diagram illustrates the ledger contents of a peer authorized to have

private data and one which is not.

Collection members may decide to share the private data with other parties if they

get into a dispute or if they want to transfer the asset to a third party. The

third party can then compute the hash of the private data and see if it matches the

state on the channel ledger, proving that the state existed between the collection

members at a certain point in time.

In some cases, you may decide to have a set of collections each comprised of a

single organization. For example an organization may record private data in their own

collection, which could later be shared with other channel members and

referenced in chaincode transactions. We’ll see examples of this in the sharing

private data topic below.

When to use a collection within a channel vs. a separate channel

Use channels when entire transactions (and ledgers) must be kept

confidential within a set of organizations that are members of the channel.

Use collections when transactions (and ledgers) must be shared among a set

of organizations, but when only a subset of those organizations should have

access to some (or all) of the data within a transaction. Additionally,

since private data is disseminated peer-to-peer rather than via blocks,

use private data collections when transaction data must be kept confidential

from ordering service nodes.

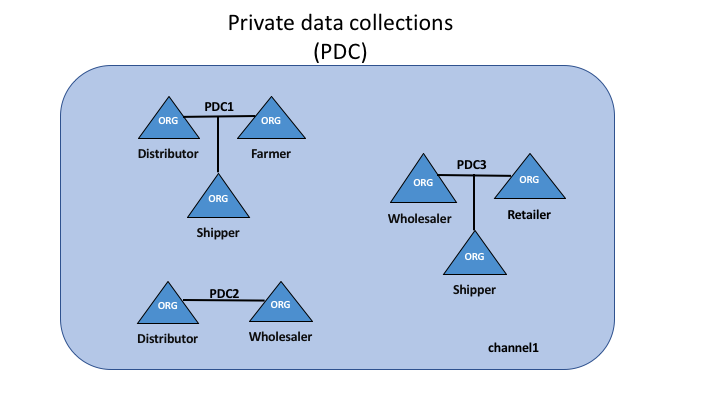

A use case to explain collections

Consider a group of five organizations on a channel who trade produce:

A Farmer selling his goods abroad

A Distributor moving goods abroad

A Shipper moving goods between parties

A Wholesaler purchasing goods from distributors

A Retailer purchasing goods from shippers and wholesalers

The Distributor might want to make private transactions with the

Farmer and Shipper to keep the terms of the trades confidential from

the Wholesaler and the Retailer (so as not to expose the markup they’re

charging).

The Distributor may also want to have a separate private data relationship

with the Wholesaler because it charges them a lower price than it does the

Retailer.

The Wholesaler may also want to have a private data relationship with the

Retailer and the Shipper.

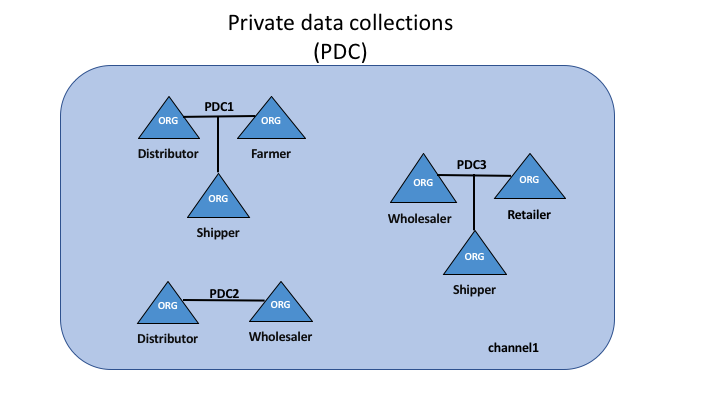

Rather than defining many small channels for each of these relationships, multiple

private data collections (PDC) can be defined to share private data between:

PDC1: Distributor, Farmer and Shipper

PDC2: Distributor and Wholesaler

PDC3: Wholesaler, Retailer and Shipper

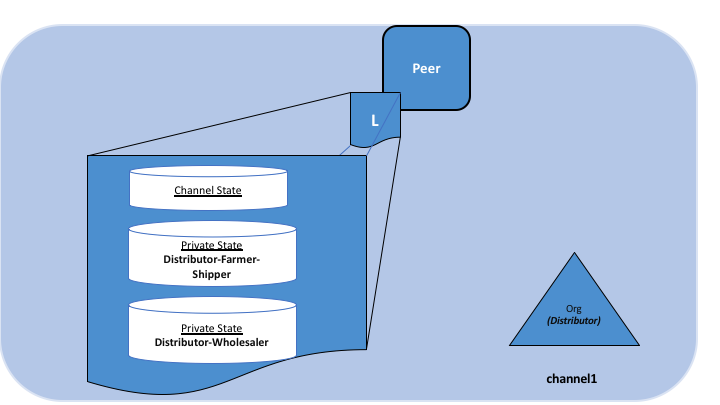

Using this example, peers owned by the Distributor will have multiple private

databases inside their ledger which includes the private data from the

Distributor, Farmer and Shipper relationship and the

Distributor and Wholesaler relationship.

Transaction flow with private data

When private data collections are referenced in chaincode, the transaction flow

is slightly different in order to protect the confidentiality of the private

data as transactions are proposed, endorsed, and committed to the ledger.

For details on transaction flows that don’t use private data refer to our

documentation on transaction flow.

The client application submits a proposal request to invoke a chaincode

function (reading or writing private data) to a target peer, which will manage

the transaction submission on behalf of the client. The client application can

specify which organizations

should endorse the proposal request, or it can delegate the

endorser selection logic

to the gateway service in the target peer. In the latter case, the gateway will

attempt to select a set of endorsing peers which are part of authorized organizations

of the collection(s) affected by the chaincode. The private data, or data used to

generate private data in chaincode, is sent in a transient field in the proposal.

The endorsing peers simulate the transaction and store the private data in

a transient data store (a temporary storage local to the peer). They

distribute the private data, based on the collection policy, to authorized peers

via gossip.

The endorsing peers send the proposal response back to the target peer. The proposal

response includes the endorsed read/write set, which includes public

data, as well as a hash of any private data keys and values. No private data is

sent back to the target peer or client. For more information on how endorsement works with

private data, click here.

The target peer verifies the proposal responses are the same before assembling the

endorsements into a transaction, which is sent back to the client for signing.

The target peer “broadcasts” the transaction (which includes the proposal

response with the private data hashes) to the ordering service. The transactions

with the private data hashes get included in blocks as normal.

The block with the private data hashes is distributed to all the peers. In this way,

all peers on the channel can validate transactions with the hashes of the private

data in a consistent way, without knowing the actual private data.

At block commit time, authorized peers use the collection policy to

determine if they are authorized to have access to the private data. If they do,

they will first check their local transient data store to determine if they

have already received the private data at chaincode endorsement time. If not,

they will attempt to pull the private data from another authorized peer. Then they

will validate the private data against the hashes in the public block and commit the

transaction and the block. Upon validation/commit, the private data is moved to

their copy of the private state database and private writeset storage. The

private data is then deleted from the transient data store.

Note: The client application can collect the endorsements instead of delegating that step to the target peer.

Refer to the v2.3 Peers and Applications topic for details.

Sharing private data

In many scenarios private data keys/values in one collection may need to be shared with

other channel members or with other private data collections, for example when you

need to transact on private data with a channel member or group of channel members

who were not included in the original private data collection. The receiving parties

will typically want to verify the private data against the on-chain hashes

as part of the transaction.

There are several aspects of private data collections that enable the

sharing and verification of private data:

First, you don’t necessarily have to be a member of a collection to write to a key in

a collection, as long as the endorsement policy is satisfied.

Endorsement policy can be defined at the chaincode level, key level (using state-based

endorsement), or collection level (starting in Fabric v2.0).

Second, starting in v1.4.2 there is a chaincode API GetPrivateDataHash() that allows

chaincode on non-member peers to read the hash value of a private key. This is an

important feature as you will see later, because it allows chaincode to verify private

data against the on-chain hashes that were created from private data in previous transactions.

This ability to share and verify private data should be considered when designing

applications and the associated private data collections.

While you can certainly create sets of multilateral private data collections to share data

among various combinations of channel members, this approach may result in a large

number of collections that need to be defined.

Alternatively, consider using a smaller number of private data collections (e.g.

one collection per organization, or one collection per pair of organizations), and

then sharing private data with other channel members, or with other

collections as the need arises. Starting in Fabric v2.0, implicit organization-specific

collections are available for any chaincode to utilize,

so that you don’t even have to define these per-organization collections when

deploying chaincode.

Private data sharing patterns

When modeling private data collections per organization, multiple patterns become available

for sharing or transferring private data without the overhead of defining many multilateral

collections. Here are some of the sharing patterns that could be leveraged in chaincode

applications:

Use a corresponding public key for tracking public state -

You can optionally have a matching public key for tracking public state (e.g. asset

properties, current ownership. etc), and for every organization that should have access

to the asset’s corresponding private data, you can create a private key/value in each

organization’s private data collection.

Chaincode access control -

You can implement access control in your chaincode, to specify which clients can

query private data in a collection. For example, store an access control list

for a private data collection key or range of keys, then in the chaincode get the

client submitter’s credentials (using GetCreator() chaincode API or CID library API

GetID() or GetMSPID() ), and verify they have access before returning the private

data. Similarly you could require a client to pass a passphrase into chaincode,

which must match a passphrase stored at the key level, in order to access the

private data. Note, this pattern can also be used to restrict client access to public

state data.

Sharing private data out of band -

As an off-chain option, you could share private data out of band with other

organizations, and they can hash the key/value to verify it matches

the on-chain hash by using GetPrivateDataHash() chaincode API. For example,

an organization that wishes to purchase an asset from you may want to verify

an asset’s properties and that you are the legitimate owner by checking the

on-chain hash, prior to agreeing to the purchase.

Sharing private data with other collections -

You could ‘share’ the private data on-chain with chaincode that creates a matching

key/value in the other organization’s private data collection. You’d pass the

private data key/value to chaincode via transient field, and the chaincode

could confirm a hash of the passed private data matches the on-chain hash from

your collection using GetPrivateDataHash(), and then write the private data to

the other organization’s private data collection.

Transferring private data to other collections -

You could ‘transfer’ the private data with chaincode that deletes the private data

key in your collection, and creates it in another organization’s collection.

Again, use the transient field to pass the private data upon chaincode invoke,

and in the chaincode use GetPrivateDataHash() to confirm that the data exists in

your private data collection, before deleting the key from your collection and

creating the key in another organization’s collection. To ensure that a

transaction always deletes from one collection and adds to another collection,

you may want to require endorsements from additional parties, such as a

regulator or auditor.

Using private data for transaction approval -

If you want to get a counterparty’s approval for a transaction before it is

completed (e.g. an on-chain record that they agree to purchase an asset for

a certain price), the chaincode can require them to ‘pre-approve’ the transaction,

by either writing a private key to their private data collection or your collection,

which the chaincode will then check using GetPrivateDataHash(). In fact, this is

exactly the same mechanism that the built-in lifecycle system chaincode uses to

ensure organizations agree to a chaincode definition before it is committed to

a channel. Starting with Fabric v2.0, this pattern

becomes more powerful with collection-level endorsement policies, to ensure

that the chaincode is executed and endorsed on the collection owner’s own trusted

peer. Alternatively, a mutually agreed key with a key-level endorsement policy

could be used, that is then updated with the pre-approval terms and endorsed

on peers from the required organizations.

Keeping transactors private -

Variations of the prior pattern can also eliminate leaking the transactors for a given

transaction. For example a buyer indicates agreement to buy on their own collection,

then in a subsequent transaction seller references the buyer’s private data in

their own private data collection. The proof of transaction with hashed references

is recorded on-chain, only the buyer and seller know that they are the transactors,

but they can reveal the pre-images if a need-to-know arises, such as in a subsequent

transaction with another party who could verify the hashes.

Coupled with the patterns above, it is worth noting that transactions with private

data can be bound to the same conditions as regular channel state data, specifically:

Key level transaction access control -

You can include ownership credentials in a private data value, so that subsequent

transactions can verify that the submitter has ownership privilege to share or transfer

the data. In this case the chaincode would get the submitter’s credentials

(e.g. using GetCreator() chaincode API or CID library API GetID() or GetMSPID() ),

combine it with other private data that gets passed to the chaincode, hash it,

and use GetPrivateDataHash() to verify that it matches the on-chain hash before

proceeding with the transaction.

Key level endorsement policies -

And also as with normal channel state data, you can use state-based endorsement

to specify which organizations must endorse transactions that share or transfer

private data, using SetPrivateDataValidationParameter() chaincode API,

for example to specify that only an owner’s organization peer, custodian’s organization

peer, or other third party must endorse such transactions.

Example scenario: Asset transfer using private data collections

The private data sharing patterns mentioned above can be combined to enable powerful

chaincode-based applications. For example, consider how an asset transfer scenario

could be implemented using per-organization private data collections:

An asset may be tracked by a UUID key in public chaincode state. Only the asset’s

ownership is recorded, nothing else is known about the asset.

The chaincode will require that any transfer request must originate from the owning client,

and the key is bound by state-based endorsement requiring that a peer from the

owner’s organization and a regulator’s organization must endorse any transfer requests.

The asset owner’s private data collection contains the private details about

the asset, keyed by a hash of the UUID. Other organizations and the ordering

service will only see a hash of the asset details.

Let’s assume the regulator is a member of each collection as well, and therefore

persists the private data, although this need not be the case.

A transaction to trade the asset would unfold as follows:

Off-chain, the owner and a potential buyer strike a deal to trade the asset

for a certain price.

The seller provides proof of their ownership, by either passing the private details

out of band, or by providing the buyer with credentials to query the private

data on their node or the regulator’s node.

Buyer verifies a hash of the private details matches the on-chain public hash.

The buyer invokes chaincode to record their bid details in their own private data collection.

The chaincode is invoked on buyer’s peer, and potentially on regulator’s peer if required

by the collection endorsement policy.

The current owner (seller) invokes chaincode to sell and transfer the asset, passing in the

private details and bid information. The chaincode is invoked on peers of the

seller, buyer, and regulator, in order to meet the endorsement policy of the public

key, as well as the endorsement policies of the buyer and seller private data collections.

The chaincode verifies that the submitting client is the owner, verifies the private

details against the hash in the seller’s collection, and verifies the bid details

against the hash in the buyer’s collection. The chaincode then writes the proposed

updates for the public key (setting ownership to the buyer, and setting endorsement

policy to be the buying organization and regulator), writes the private details to the

buyer’s private data collection, and potentially deletes the private details from seller’s

collection. Prior to final endorsement, the endorsing peers ensure private data is

disseminated to any other authorized peers of the seller and regulator.

The seller submits the transaction with the public data and private data hashes

for ordering, and it is distributed to all channel peers in a block.

Each peer’s block validation logic will consistently verify the endorsement policy

was met (buyer, seller, regulator all endorsed), and verify that public and private

state that was read in the chaincode has not been modified by any other transaction

since chaincode execution.

All peers commit the transaction as valid since it passed validation checks.

Buyer peers and regulator peers retrieve the private data from other authorized

peers if they did not receive it at endorsement time, and persist the private

data in their private data state database (assuming the private data matched

the hashes from the transaction).

With the transaction completed, the asset has been transferred, and other

channel members interested in the asset may query the history of the public

key to understand its provenance, but will not have access to any private

details unless an owner shares it on a need-to-know basis.

The basic asset transfer scenario could be extended for other considerations,

for example the transfer chaincode could verify that a payment record is available

to satisfy payment versus delivery requirements, or verify that a bank has

submitted a letter of credit, prior to the execution of the transfer chaincode.

And instead of transactors directly hosting peers, they could transact through

custodian organizations who are running peers.

Purging private data

For very sensitive data, even the parties sharing the private data might want

— or might be required by government regulations — to periodically “purge” the data

on their peers, leaving behind a hash of the data on the blockchain

to serve as immutable evidence of the private data.

In some of these cases, the private data only needs to exist in the peer’s private

database until it can be replicated into a database external to the peer’s

blockchain. The data might also only need to exist on the peers until a chaincode business

process is done with it (trade settled, contract fulfilled, etc).

To support these use cases, private data can be purged so that it is not available for chaincode queries, not available in block events, and not available for other peers requesting the private data.

Purging private data in chaincode

Private data can be deleted from state just like regular state data so that it is not available for query in chaincode for future transactions.

However, when private data is simply deleted from state, the history of the private data remains in the peer’s private database so that it can be returned in block events and returned to other peers that are catching up to the current block height.

If you need to completely remove the private data from all peers that have access to it, use the chaincode API PurgePrivateData instead of the DelPrivateData API.

Purging private data automatically

Private data collections can be configured to purge private data automatically if it has not been modified for a configurable number of blocks.

How a private data collection is defined

For more details on collection definitions, and other low level information about

private data and collections, refer to the private data reference topic.