Chaincode namespace¶

Audience: Architects, application and smart contract developers, administrators

A chaincode namespace allows it to keep its world state separate from other chaincodes. Specifically, smart contracts in the same chaincode share direct access to the same world state, whereas smart contracts in different chaincodes cannot directly access each other’s world state. If a smart contract needs to access another chaincode world state, it can do this by performing a chaincode-to-chaincode invocation. Finally, a blockchain can contain transactions which relate to different world states.

In this topic, we’re going to cover:

- The importance of namespaces

- What is a chaincode namespace

- Channels and namespaces

- How to use chaincode namespaces

- How to access world states across smart contracts

- Design considerations for chaincode namespaces

Motivation¶

A namespace is a common concept. We understand that Park Street, New York and Park Street, Seattle are different streets even though they have the same name. The city forms a namespace for Park Street, simultaneously providing freedom and clarity.

It’s the same in a computer system. Namespaces allow different users to program and operate different parts of a shared system, without getting in each other’s way. Many programming languages have namespaces so that programs can freely assign unique identifiers, such as variable names, without worrying about other programs doing the same. We’ll see that Hyperledger Fabric uses namespaces to help smart contracts keep their ledger world state separate from other smart contracts.

Scenario¶

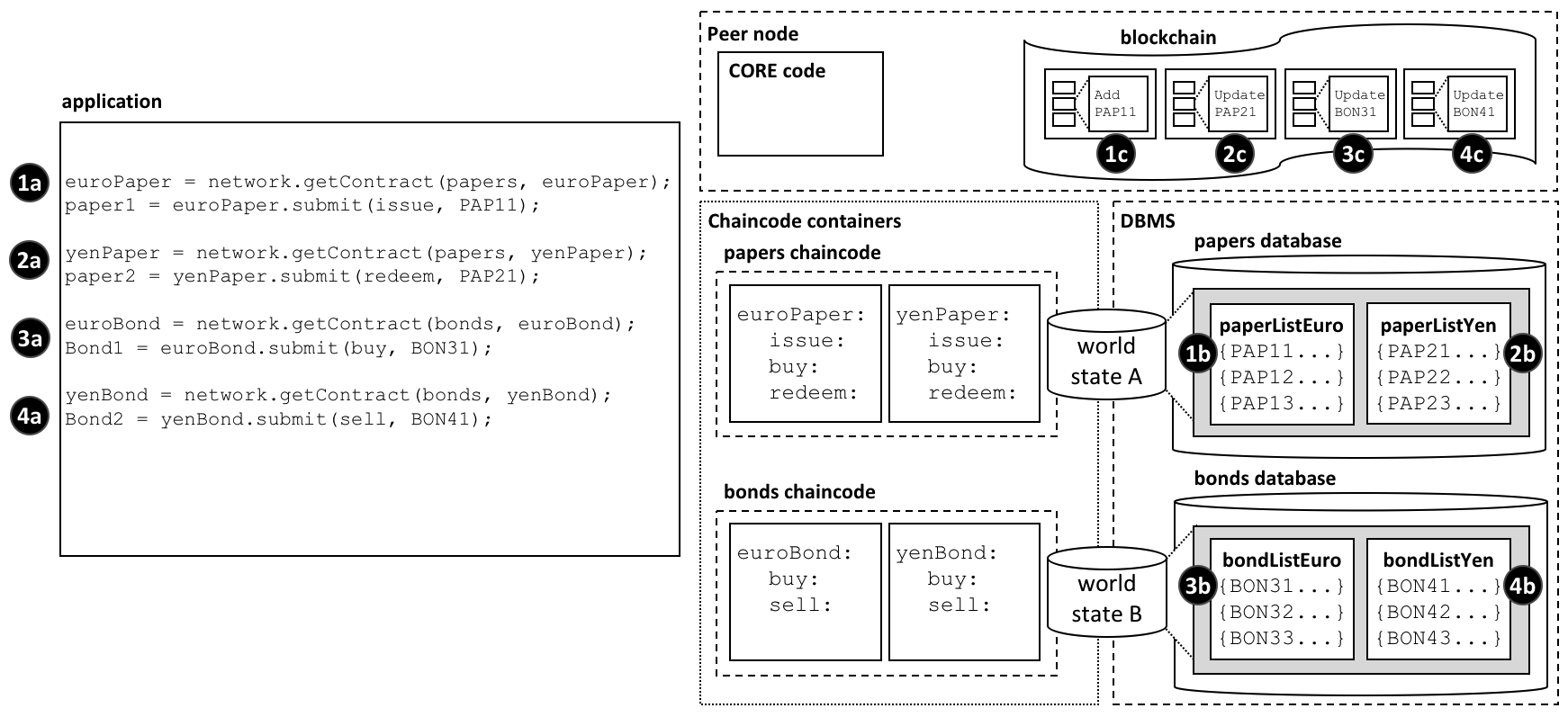

Let’s examine how the ledger world state organizes facts about business objects that are important to the organizations in a channel using the diagram below. Whether these objects are commercial papers, bonds, or vehicle registrations, and wherever they are in their lifecycle, they are maintained as states within the ledger world state database. A smart contract manages these business objects by interacting with the ledger (world state and blockchain), and in most cases this will involve it querying or updating the ledger world state.

It’s vitally important to understand that the ledger world state is partitioned according to the chaincode of the smart contract that accesses it, and this partitioning, or namespacing is an important design consideration for architects, administrators and programmers.

The ledger world state is

separated into different namespaces according to the chaincode that accesses it.

Within a given channel, smart contracts in the same chaincode share the same

world state, and smart contracts in different chaincodes cannot directly access

each other’s world state. Likewise, a blockchain can contain transactions that

relate to different chaincode world states.

The ledger world state is

separated into different namespaces according to the chaincode that accesses it.

Within a given channel, smart contracts in the same chaincode share the same

world state, and smart contracts in different chaincodes cannot directly access

each other’s world state. Likewise, a blockchain can contain transactions that

relate to different chaincode world states.

In our example, we can see four smart contracts defined in two different

chaincodes, each of which is in their own chaincode container. The euroPaper

and yenPaper smart contracts are defined in the papers chaincode. The

situation is similar for the euroBond and yenBond smart contracts – they

are defined in the bonds chaincode. This design helps application programmers

understand whether they are working with commercial papers or bonds priced in

Euros or Yen, and because the rules for each financial product don’t really

change for different currencies, it makes sense to manage their deployment in

the same chaincode.

The diagram also shows the consequences of this deployment choice.

The database management system (DBMS) creates different world state databases

for the papers and bonds chaincodes and the smart contracts contained within

them. World state A and world state B are each held within distinct

databases; the data are isolated from each other such that a single world state

query (for example) cannot access both world states. The world state is said to

be namespaced according to its chaincode.

See how world state A contains two lists of commercial papers paperListEuro

and paperListYen. The states PAP11 and PAP21 are instances of each paper

managed by the euroPaper and yenPaper smart contracts respectively. Because

they share the same chaincode namespace, their keys (PAPxyz) must be unique

within the namespace of the papers chaincode, a little like a street name is

unique within a town. Notice how it would be possible to write a smart contract

in the papers chaincode that performed an aggregate calculation over all the

commercial papers – whether priced in Euros or Yen – because they share the

same namespace. The situation is similar for bonds – they are held within

world state B which maps to a separate bonds database, and their keys must

be unique.

Just as importantly, namespaces mean that euroPaper and yenPaper cannot

directly access world state B, and that euroBond and yenBond cannot

directly access world state A. This isolation is helpful, as commercial papers

and bonds are very distinct financial instruments; they have different

attributes and are subject to different rules. It also means that papers and

bonds could have the same keys, because they are in different namespaces. This

is helpful; it provides a significant degree of freedom for naming. Use this

freedom to name different business objects meaningfully.

Most importantly, we can see that a blockchain is associated with the peer

operating in a particular channel, and that it contains transactions that affect

both world state A and world state B. That’s because the blockchain is the

most fundamental data structure contained in a peer. The set of world states can

always be recreated from this blockchain, because they are the cumulative

results of the blockchain’s transactions. A world state helps simplify smart

contracts and improve their efficiency, as they usually only require the current

value of a state. Keeping world states separate via namespaces helps smart

contracts isolate their logic from other smart contracts, rather than having to

worry about transactions that correspond to different world states. For example,

a bonds contract does not need to worry about paper transactions, because it

cannot see their resultant world state.

It’s also worth noticing that the peer, chaincode containers and DBMS all are logically different processes. The peer and all its chaincode containers are always in physically separate operating system processes, but the DBMS can be configured to be embedded or separate, depending on its type. For LevelDB, the DBMS is wholly contained within the peer, but for CouchDB, it is a separate operating system process.

It’s important to remember that namespace choices in this example are the result of a business requirement to share commercial papers in different currencies but isolate them separate from bonds. Think about how the namespace structure would be modified to meet a business requirement to keep every financial asset class separate, or share all commercial papers and bonds?

Channels¶

If a peer is joined to multiple channels, then a new blockchain is created and managed for each channel. Moreover, every time a chaincode is deployed to a new channel, a new world state database is created for it. It means that the channel also forms a kind of namespace alongside that of the chaincode for the world state.

However, the same peer and chaincode container processes can be simultaneously joined to multiple channels – unlike blockchains, and world state databases, these processes do not increase with the number of channels joined.

For example, if you deployed the papers and bonds chaincode to a new

channel, there would a totally separate blockchain created, and two new world

state databases created. However, the peer and chaincode containers would not

increase; each would just be connected to multiple channels.

Usage¶

Let’s use our commercial paper example to show how an application uses a smart contract with namespaces. It’s worth noting that an application communicates with the peer, and the peer routes the request to the appropriate chaincode container which then accesses the DBMS. This routing is done by the peer core component shown in the diagram.

Here’s the code for an application that uses both commercial papers and bonds, priced in Euros and Yen. The code is fairly self-explanatory:

const euroPaper = network.getContract(papers, euroPaper);

paper1 = euroPaper.submit(issue, PAP11);

const yenPaper = network.getContract(papers, yenPaper);

paper2 = yenPaper.submit(redeem, PAP21);

const euroBond = network.getContract(bonds, euroBond);

bond1 = euroBond.submit(buy, BON31);

const yenBond = network.getContract(bonds, yenBond);

bond2 = yenBond.submit(sell, BON41);

See how the application:

- Accesses the

euroPaperandyenPapercontracts using thegetContract()API specifying thepaperschaincode. See interaction points 1a and 2a. - Accesses the

euroBondandyenBondcontracts using thegetContract()API specifying thebondschaincode. See interaction points 3a and 4a. - Submits an

issuetransaction to the network for commercial paperPAP11using theeuroPapercontract. See interaction point 1a. This results in the creation of a commercial paper represented by statePAP11inworld state A; interaction point 1b. This operation is captured as a transaction in the blockchain at interaction point 1c. - Submits a

redeemtransaction to the network for commercial paperPAP21using theyenPapercontract. See interaction point 2a. This results in the creation of a commercial paper represented by statePAP21inworld state A; interaction point 2b. This operation is captured as a transaction in the blockchain at interaction point 2c. - Submits a

buytransaction to the network for bondBON31using theeuroBondcontract. See interaction point 3a. This results in the creation of a bond represented by stateBON31inworld state B; interaction point 3b. This operation is captured as a transaction in the blockchain at interaction point 3c. - Submits a

selltransaction to the network for bondBON41using theyenBondcontract. See interaction point 4a. This results in the creation of a bond represented by stateBON41inworld state B; interaction point 4b. This operation is captured as a transaction in the blockchain at interaction point 4c.

See how smart contracts interact with the world state:

euroPaperandyenPapercontracts can directly accessworld state A, but cannot directly accessworld state B.World state Ais physically held in thepapersdatabase in the database management system (DBMS) corresponding to thepaperschaincode.euroBondandyenBondcontracts can directly accessworld state B, but cannot directly accessworld state A.World state Bis physically held in thebondsdatabase in the database management system (DBMS) corresponding to thebondschaincode.

See how the blockchain captures transactions for all world states:

- Interactions 1c and 2c correspond to transactions create and update

commercial papers

PAP11andPAP21respectively. These are both contained withinworld state A. - Interactions 3c and 4c correspond to transactions both update bonds

BON31andBON41. These are both contained withinworld state B. - If

world state Aorworld state Bwere destroyed for any reason, they could be recreated by replaying all the transactions in the blockchain.

Cross chaincode access¶

As we saw in our example scenario, euroPaper and yenPaper

cannot directly access world state B. That’s because we have designed our

chaincodes and smart contracts so that these chaincodes and world states are

kept separately from each other. However, let’s imagine that euroPaper needs

to access world state B.

Why might this happen? Imagine that when a commercial paper was issued, the

smart contract wanted to price the paper according to the current return on

bonds with a similar maturity date. In this case it will be necessary for the

euroPaper contract to be able to query the price of bonds in world state B.

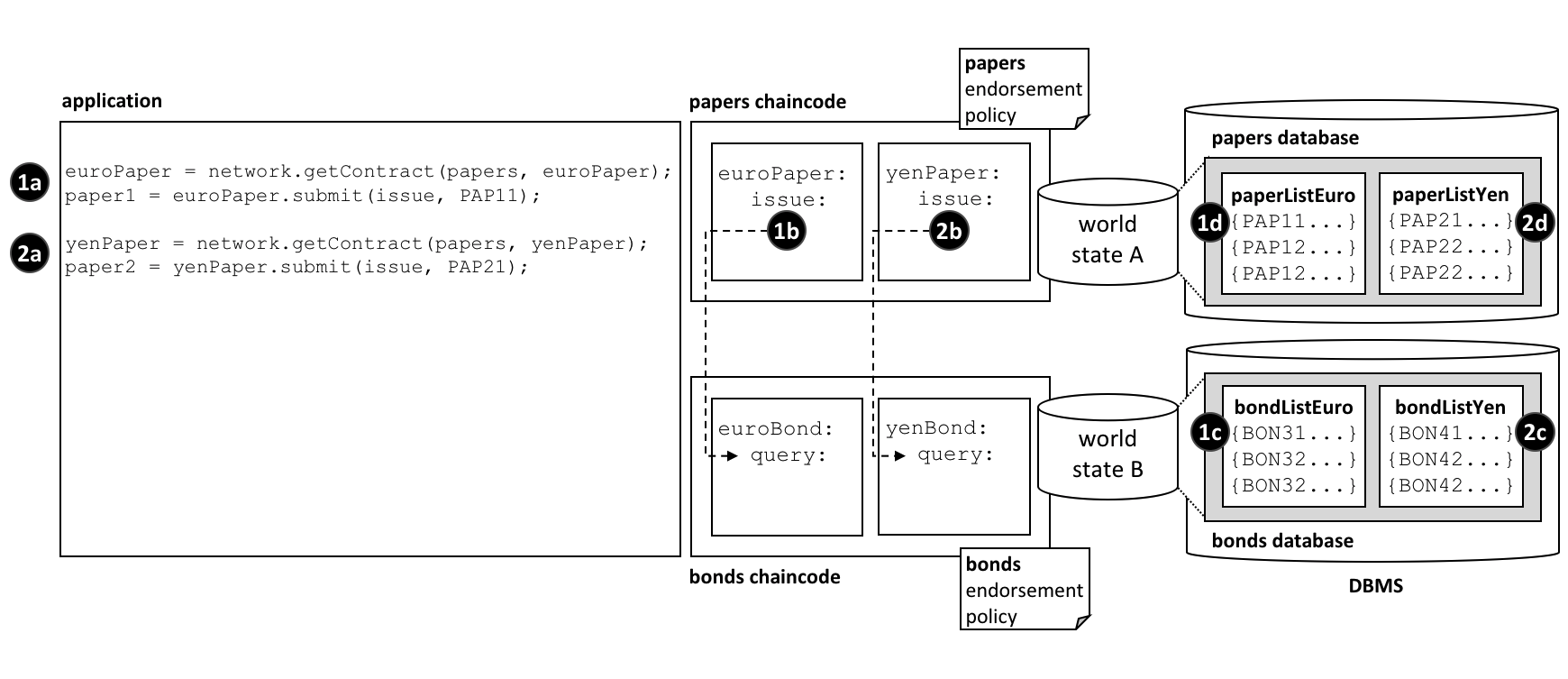

Look at the following diagram to see how we might structure this interaction.

How chaincodes and smart

contracts can indirectly access another world state – via its chaincode.

How chaincodes and smart

contracts can indirectly access another world state – via its chaincode.

Notice how:

- the application submits an

issuetransaction in theeuroPapersmart contract to issuePAP11. See interaction 1a. - the

issuetransaction in theeuroPapersmart contract calls thequerytransaction in theeuroBondsmart contract. See interaction point 1b. - the

queryineuroBondcan retrieve information fromworld state B. See interaction point 1c. - when control returns to the

issuetransaction, it can use the information in the response to price the paper and updateworld state Awith information. See interaction point 1d. - the flow of control for issuing commercial paper priced in Yen is the same. See interaction points 2a, 2b, 2c and 2d.

Control is passed between chaincode using the invokeChaincode()

API.

This API passes control from one chaincode to another chaincode.

Although we have only discussed query transactions in the example, it is possible to invoke a smart contract which will update the called chaincode’s world state. See the considerations below.

Considerations¶

- In general, each chaincode will have a single smart contract in it.

- Multiple smart contracts should only be deployed in the same chaincode if they are very closely related. Usually, this is only necessary if they share the same world state.

- Chaincode namespaces provide isolation between different world states. In general it makes sense to isolate unrelated data from each other. Note that you cannot choose the chaincode namespace; it is assigned by Hyperledger Fabric, and maps directly to the name of the chaincode.

- For chaincode to chaincode interactions using the

invokeChaincode()API, both chaincodes must be installed on the same peer.- For interactions that only require the called chaincode’s world state to be queried, the invocation can be in a different channel to the caller’s chaincode.

- For interactions that require the called chaincode’s world state to be updated, the invocation must be in the same channel as the caller’s chaincode.